Saturday, August 15, 2009

Folk art

Defining Folk Art, it seems, is a difficult process. It would be easy to give a glib, shallow definition such as, ‘art that folk make’, but of course it is much more complex than that. One must take into account the nationalistic, the radical, and the existential reasons behind this kind of art practise(24).

Creativity and order within a nationalistic conception means that symbols and shapes are accepted by the larger community, but at the same time are appropriated by the individual, and in turn re-accepted back into the community. The art- work can be uniquely the artist’s and the community’s at the same time[i].

The radical definition characteristically is often based in a reaction to a sense of change. For example, ”if the modern world is too individualistic, full of freedom but broken by greed and alienation the folklore is defined as collective, communal, unifying.” This kind of reaction follows also according to other changes. If the ‘new’ progress is “too materialistic, comfortable but shallow” the reaction may be spiritual(25).

Ultimately folk art will usually be part of a continuum that will show continuity of time and will help define particular cultures’ style.(26)

Existentialism is ultimately a definition of the present. It seems to be about the artistic individual in real situations evolving. “Folklore, existentially, is the unification of the creative individual with the collective through mutual action.”

As an aside, I do not wish to dwell here for too long. Folk Art does tend to be categorised in to the realm of craft. The argument of art and craft, that is for other people to nut out, I personally believe that it is a moot point in this day and age, (Louise Weaver and Rosalind Piggot are examples of this.) Painting and sculpture are considered ‘art’ by the mainstream, bad painting and sculpture are just that, bad. It is not as though it does not exist, but still it will get the title of ‘art’. Where as, a finely hand woven piece of cloth could still be called craft no matter how aesthetically beautiful it is.(27)

The main reason I am drawn to Folk Art is the infinite possibilities of inventiveness, decoration, characterisation, composition and freedom. Looking through books from different countries I can glean so many ideas and adapt them to my own art practice. For example, model making, sewing, small sculptures, home altars, mixing media and different ways of presentation. When looking at masks, sculptures or textiles you can see that each piece is imbued with meaning that is either apparent or falls within a vast history of making and refining, that is interesting to me.

[i] Ibid. p. 26

Creativity and order within a nationalistic conception means that symbols and shapes are accepted by the larger community, but at the same time are appropriated by the individual, and in turn re-accepted back into the community. The art- work can be uniquely the artist’s and the community’s at the same time[i].

The radical definition characteristically is often based in a reaction to a sense of change. For example, ”if the modern world is too individualistic, full of freedom but broken by greed and alienation the folklore is defined as collective, communal, unifying.” This kind of reaction follows also according to other changes. If the ‘new’ progress is “too materialistic, comfortable but shallow” the reaction may be spiritual(25).

Ultimately folk art will usually be part of a continuum that will show continuity of time and will help define particular cultures’ style.(26)

Existentialism is ultimately a definition of the present. It seems to be about the artistic individual in real situations evolving. “Folklore, existentially, is the unification of the creative individual with the collective through mutual action.”

As an aside, I do not wish to dwell here for too long. Folk Art does tend to be categorised in to the realm of craft. The argument of art and craft, that is for other people to nut out, I personally believe that it is a moot point in this day and age, (Louise Weaver and Rosalind Piggot are examples of this.) Painting and sculpture are considered ‘art’ by the mainstream, bad painting and sculpture are just that, bad. It is not as though it does not exist, but still it will get the title of ‘art’. Where as, a finely hand woven piece of cloth could still be called craft no matter how aesthetically beautiful it is.(27)

The main reason I am drawn to Folk Art is the infinite possibilities of inventiveness, decoration, characterisation, composition and freedom. Looking through books from different countries I can glean so many ideas and adapt them to my own art practice. For example, model making, sewing, small sculptures, home altars, mixing media and different ways of presentation. When looking at masks, sculptures or textiles you can see that each piece is imbued with meaning that is either apparent or falls within a vast history of making and refining, that is interesting to me.

[i] Ibid. p. 26

Miniatures

I take on the concept of the tiny. The miniature is the product of the whim of the artisan. Small objects often become toys for children; their dimensions come into perspective for the child. Is playing with toys a rehearsal for adult hood? The sense of fun and whimsy gives the object life and encourages a sense of freedom.

“Mexico opposed the expression referring to a monumental spirit by taking pleasure in creating art in its most minute scale, the very tiny, product of the most detailed observation, in an extreme and trained technique of manual dexterity…

Mexican production of artwork on a reduced scale does not develop a feeling for decorative miniatures, as is the case in many ancient cultures or in worlds far distant from western influence. Nor is it directly related to the use of European miniature techniques, recreated in the ostentation of the medieval task of reducing the illustration to clarify the text. In Mexico there is a touching delight in the use or possession of something very tiny…”(29)

Sometimes I feel that there is a challenge in reducing the scale of imagery and structure. There is the ability to manipulate the viewer, to stop them and make them step up to the work, and to get very close to it and really look at it. The emotional response to such work is echoed in the above passage. When work is of a ‘hand held’ dimension I think that the urge to have that object is universal.

“ The well-liked art, repetitive and so full of meanings which are given to diminutive dimensions in Mexico, seems to become a part of the craftsman’s fingers when he creates art that revels in the minute details which require the use of a magnifying glass in order to be admired…How else can one explain the unique custom of dressing fleas? Or carving scenes in fruit pits? Or creating an orchestra, with its musicians and their instruments, none of them over two centimetres tall? What Lilliputian universe is present in the Puebla toy that features a showcase inside a nutshell? Why do Oaxacan women take such pains to include eyes on the tiny faces they embroider on a dress, when these cannot readily be seen by the naked eye?”(30)

Why do these artisans make such tiny, microscopic work? I assume from my own experience, that in the ‘tiny’ one can hide things and put secrets into objects. In relation to the Mexicans, their work is full of folklore, magic. Superstition and tradition. Above all their innate skill allows them the freedom and ability to fulfil such whimsical inspirations.

“Mexico opposed the expression referring to a monumental spirit by taking pleasure in creating art in its most minute scale, the very tiny, product of the most detailed observation, in an extreme and trained technique of manual dexterity…

Mexican production of artwork on a reduced scale does not develop a feeling for decorative miniatures, as is the case in many ancient cultures or in worlds far distant from western influence. Nor is it directly related to the use of European miniature techniques, recreated in the ostentation of the medieval task of reducing the illustration to clarify the text. In Mexico there is a touching delight in the use or possession of something very tiny…”(29)

Sometimes I feel that there is a challenge in reducing the scale of imagery and structure. There is the ability to manipulate the viewer, to stop them and make them step up to the work, and to get very close to it and really look at it. The emotional response to such work is echoed in the above passage. When work is of a ‘hand held’ dimension I think that the urge to have that object is universal.

“ The well-liked art, repetitive and so full of meanings which are given to diminutive dimensions in Mexico, seems to become a part of the craftsman’s fingers when he creates art that revels in the minute details which require the use of a magnifying glass in order to be admired…How else can one explain the unique custom of dressing fleas? Or carving scenes in fruit pits? Or creating an orchestra, with its musicians and their instruments, none of them over two centimetres tall? What Lilliputian universe is present in the Puebla toy that features a showcase inside a nutshell? Why do Oaxacan women take such pains to include eyes on the tiny faces they embroider on a dress, when these cannot readily be seen by the naked eye?”(30)

Why do these artisans make such tiny, microscopic work? I assume from my own experience, that in the ‘tiny’ one can hide things and put secrets into objects. In relation to the Mexicans, their work is full of folklore, magic. Superstition and tradition. Above all their innate skill allows them the freedom and ability to fulfil such whimsical inspirations.

Mexican home altars

Mexican Domestic Shrines are like miniature stages, a surreal juxtaposing of seemingly unrelated objects to create a narrative of Mexican Christianity.(31) Throughout rural Mexico, the home altar represents much about the inhabitants of the home, their tradition and culture. Altars are created to honour spirits and gods on a day-to-day basis and especially during Christmas and Day of the Dead celebrations.

What attracts me to these assemblages is, the unique aesthetic in which disparate objects are gathered together and layered and arranged to create highly original and personal representations of their creators devotion. All this achieved in an instinctive and evolving way. I particularly like the way clearly western objects like plastic ‘cupie’ dolls are included and appropriated to take on a new adopted meaning. When a non-Mexican viewer looks at the altar, they can be confusing and sometimes funny seeing what might be a Fred Flintstone or Bart Simpson doll strung up to a cross like some kind of Jesus. The subversive intent behind these inclusions is mysterious. Is the maker trying to poke fun at the Roman Catholic Church? Or is it a matter of necessity that one needs a doll to play Christ and finds Bart Simpson, knowing nothing of his former life as a TV star?

What attracts me to these assemblages is, the unique aesthetic in which disparate objects are gathered together and layered and arranged to create highly original and personal representations of their creators devotion. All this achieved in an instinctive and evolving way. I particularly like the way clearly western objects like plastic ‘cupie’ dolls are included and appropriated to take on a new adopted meaning. When a non-Mexican viewer looks at the altar, they can be confusing and sometimes funny seeing what might be a Fred Flintstone or Bart Simpson doll strung up to a cross like some kind of Jesus. The subversive intent behind these inclusions is mysterious. Is the maker trying to poke fun at the Roman Catholic Church? Or is it a matter of necessity that one needs a doll to play Christ and finds Bart Simpson, knowing nothing of his former life as a TV star?

Outsider art

Art Brut, Raw Art, Outsider Art and Naive Art are terms used to describe a kind of art making that has often fallen between the cracks of formal, educated art school art. Jean Dubuffet (who is responsible for bringing this art into the public forum) describes Art Brut in an essay entitled l’art brut prefere aux culturels, as “ works of every kind- Drawings, paintings, embroideries, carved or modelled figures, etc.- presenting a spontaneous, highly inventive character, as little beholden as possible to the ordinary run of art or to cultural conventions, the makers of them being obscure persons foreign to professional art circles. We mean by this the works executed by people untouched by artistic culture, works in which imitation- has little or no part, so that their makers derive everything (subjects, choice of materials used, means of transposition, rhythms, ways of patterning, etc.) from their own resources and not from the conventions of classic art or the art that happens to be fashionable”(32).

As part of my own artistic history, it may be worth mentioning here that I was an instructor at a disability art program for two years. While I was working in that position I gained first hand experience of the creative processes of people with disabilities. I already had an interest in Outsider Art, so the opportunity to experience the work being made was fascinating. The automatic and instinctual marks made by these artists, and the compulsive intent they expended was inspirational. As an artist myself I try to incorporate these making processes into my own work. In watching these artists with disabilities approach and make their work I discovered that often there was not a lot of introspective criticism. Often an artist would repeat the same motif over and over to create a repetitive pattern or fill a whole book with drawings or collaged pictures. The final outcome was not a consideration at the beginning of the process. After being at art school for four years this approach to making was liberating.

“ …The paintings created by untrained artists whose position in society was often obscure and humble suggested to many an innocence and a spontaneity in refreshing contrast to the works produced by painters inculcated with formal techniques”(33).

“ As for madness, the surrealists saw it as a creative rather than a destructive condition, something more positive than negative.”(34)

As part of my own artistic history, it may be worth mentioning here that I was an instructor at a disability art program for two years. While I was working in that position I gained first hand experience of the creative processes of people with disabilities. I already had an interest in Outsider Art, so the opportunity to experience the work being made was fascinating. The automatic and instinctual marks made by these artists, and the compulsive intent they expended was inspirational. As an artist myself I try to incorporate these making processes into my own work. In watching these artists with disabilities approach and make their work I discovered that often there was not a lot of introspective criticism. Often an artist would repeat the same motif over and over to create a repetitive pattern or fill a whole book with drawings or collaged pictures. The final outcome was not a consideration at the beginning of the process. After being at art school for four years this approach to making was liberating.

“ …The paintings created by untrained artists whose position in society was often obscure and humble suggested to many an innocence and a spontaneity in refreshing contrast to the works produced by painters inculcated with formal techniques”(33).

“ As for madness, the surrealists saw it as a creative rather than a destructive condition, something more positive than negative.”(34)

Freakery

As mentioned in the introduction, I have had quite a few problems making artwork about freaks and side shows exhibits. It is a huge fascination for me but at the same time hugely disturbing. I guess I haven’t been able to work out a new way of thinking about these people so I can turn them into characters that will fit in with my existing characters. I think the main issue I have is a moral and ethical one. I have been reading about specific people with specific conditions, and it is fascinating, but is it wrong to revive a dubious form of entertainment via visual prompts? I don’t know; it could be acceptable for someone else. It isn’t very nice to stare at people with a disability, and I thought that if I read enough anecdotes about side show exhibits I would be able to become desensitised to the material and just make work. This however had the opposite effect, now I find it a sad task to look at the photographs of sideshow folk. When I first became interested in human oddities of the past, I thought that it was good that they could gain employment in side shows and have the support of other unusual people like themselves and that they weren’t alone. Obviously it must have been difficult to gain employment doing other jobs. Of course, when I worked with people with disabilities I didn’t think that they should be in the circus or side show, on the contrary, I thought that most of them, with a little assistance would be able to achieve quite a lot for themselves in their lives. So, the contrasting ideas about the past and today really do collide when discussing this topic. I have been lucky in finding a resource called Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body edited by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, New York University Press 1996. I have derived most of my information regarding human oddities from this book. This text I have found to be exceedingly insightful, as it is a collection of essays about many different aspects of sideshow, circus, museums, collecting, racism, prejudice and Micheal Jackson.

“ It wasn’t until the 1840s that the word freak became connected with human abnormalities”.(35) Monster, Oddity and Curiosity were all used at different times to describe the generations of people who were displayed for entertainment, ‘scientific’ investigation and for profit.

“ In Victorian America the exhibition of freaks exploded into a public ritual that bonded a sundering polity together in the collective act of looking”.(36)

We now call the same people ‘physically disabled’ and hopefully would show them the curtesy of not staring and pointing. To use the word ‘freak’ to describe such a person now is seen in the poorest possible taste. We are more inclined to whisper the word in context of some one who has altered their own body on purpose to draw attention. For example, tattoos of the body and face, piercings, shaving and colouring hair and dressing outrageously. The other way the word ‘freak’ is used, is to describe a state of mind. “I freaked out”, that means, I couldn’t cope, I went berserk. And, “Something freaky happened”; it was surprising, unexpected and strange. So from this point on when the word freak is used, I am not using it in relation to these contemporary definitions, but rather in relation to a historical reference.

“ The modern freak show was a response to the growing mass market for amusements generated by urbanisation and economic growth. The New York City entrepreneur P.T. Barnum (1810-91) pioneered the modern exhibition of physically anomalous individuals at his American Museum, a popular, inexpensive pleasure palace. For the next century, in its various guises, the freak show remained a widely proliferated, popular, and highly conventionalised form of amusement in both Europe and North America. By 1950 because of a combination of the new, medicalized understandings of physical anomalies, the growth of concern for minority rights, and the rise of alternative forms of amusement such as television and the movies, the freak show had begun to decline.”(37) The preoccupation with those who are different from ourselves has been with us for most of human existence, either through ethnic difference, birth defects or any number of other more subtle reasons. It is thought that perhaps this is so because we fear being different to those around us that we do not want to stand out, (this is also a fear of those with the disability, “that the only way he would be able to make a living would be displaying himself in a sideshow.”(38)) Also, those who display difference can act as a reflection of what we fear we may become. The fragility of the human body also is apparent and becomes interesting and scary.

This chapter has turned out completely differently from how I would have imagined eighteen months ago. Originally I would have written about specific “freaks” and I imagine I may not have been so sensitive to the subject matter as I am now. It may have made more ‘entertaining’ reading, but this is where I’m at now with this subject. I expect this transformation in thinking is what research is about.

The Careers of People Exhibited in Freak Shows: The Problem of Volition and Valorization by David A. Gerber is an essay taken from the above-mentioned book. In this article Gerber discusses the concept of the right of consent and choice in relation to a book written by Robert Bogdan called Freak show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (1988). I have not read Bogdan’s book myself, only extracts presented by Gerber for use in this discussion.

On the face of it, Bogdan’s approach seems reasonable. When his five-point definition is investigated, I think he gives a lot of credit to the intellect of the common man circa 1840-1940.

‘Freak’ it seems was a broad way of grouping a lot of different physical types together under one literal banner. According to Bogdan, ““Freak” is an invention or construct, not a person, so the display of such people is not an offense to humanity but, more or less, show business.”(39) This is a logical and reasonable explanation. It separates ‘freak’ from the individual and is used in a way like ‘vaudeville’ is used as a description of a performance. The problem for me is, if a person works for a vaudeville show, that makes them a vaudevillian. If a person works for a freak show, it would make them a freak. So in reality one cannot separate the ‘humanity’ from the construct. Point two is, “historically the freak show has constituted a legitimate performance, because it was consciously staged for commercial and artistic success”.(40) I have no argument with this statement, however, point three, “the freak show ultimately was founded upon the willing participation of those displayed, the majority of whom were “active participants” in creating their presentations and found value and status in their roles as human exhibits”.(41) There are troubling combinations of words in this sentence. Willing participation, active participants, value and status and human exhibits. Firstly, this doesn’t match the first point where Bogdan says ‘freak’ is a construct, not a person, and here he says there is willing and active participation and value and status to be a human exhibit. Willing and active participation does not sit well with me.

“ Choice and consent continue to be problematic precisely because of the role of circumstances, such as the accident of the social situation into which we are born, in our lives, and because we are not equal in power to influence the course of our lives or even to understand them”.(42) Even the most educated, healthy individuals make bad decisions sometimes. So is the choice ‘actively’ positive when a person suffering a disability worthy of the freak show decides, “that’s the life for me?” The decision is not a fair one. Does the individual have more than one source for an income? Has the individual got all the correct information and understand it? Do they have enough time to decide? Is the individual being pressured or bullied into their decision? Is the individual in a situation where s/he can decide not to choose? These are very important factors in choice, ones that contemporary society may take for granted.

The ‘value and status’ perspective that Bogdan takes is obviously one of taking freak show participants stories at face value. If one is making choices about ones life without all the information or support as the above paragraph illustrates, then of course the individual will know nothing else, and hopefully would make the best of things, as is human nature. It seems a common thread among freak show performers that they saw themselves not as victims, but rather held their audience in contempt. The audience were the victims as they were the ones parting with their money. Sex workers defending their profession and their choice to persevere in this line of employment also use this argument. The value and status alluded to by Bogdan is rather tenuous. There may have been value and status from within the freak show, among co-workers. But I really do not think that value or status existed out side that arena.

As far as Bogdans statement “we need to question our assumption that we have a legitimate claim to argue with and condemn the choices, such as participating in a freak show, of those who lived in other historical epochs, especially when they saw no moral issue in their activities”(43). If social history is not looked back on with out a sense of moral judgement, the way we move into the future can have a precarious aim and outcome. Just because Bogdan doesn’t think we have a legitimate claim to pass judgement over those who lived during a different time, certainly doesn’t mean that we can’t and shouldn’t. Above all, I find it difficult to believe that those involved in the participation of freak shows found no moral dilemma in that participation.

And finally, “the freak show is a long gone phenomenon, so it is useless to condemn it.”(44) Even though it may seem like an extreme comparison, the Second World War and the atrocities delivered to people with disabilities, gypsies, the elderly and of course the Jews, also happened a long time ago, does that mean that it is also useless to condemn that?

I may be taking a hard line with Bogdans point of view, but I believe that it is this kind of insidious sentiment that keeps tabloids and voyeuristic television flourishing. I am not passing moral judgement on the fact that all this still exists in a different form, because I am just as guilty as the next person of looking. I am suggesting that one should take into account what is this kind of ‘entertainment’ actually providing society with? It’s easy to imagine in the future, a similar passage to Bogdan’s being written about the tragedy of Michael Jackson or Pamela Anderson. Most of the points listed by Bogdan could directly relate to them. So it seems the freak show is rolling on, so is it useless to condemn it?

“ It wasn’t until the 1840s that the word freak became connected with human abnormalities”.(35) Monster, Oddity and Curiosity were all used at different times to describe the generations of people who were displayed for entertainment, ‘scientific’ investigation and for profit.

“ In Victorian America the exhibition of freaks exploded into a public ritual that bonded a sundering polity together in the collective act of looking”.(36)

We now call the same people ‘physically disabled’ and hopefully would show them the curtesy of not staring and pointing. To use the word ‘freak’ to describe such a person now is seen in the poorest possible taste. We are more inclined to whisper the word in context of some one who has altered their own body on purpose to draw attention. For example, tattoos of the body and face, piercings, shaving and colouring hair and dressing outrageously. The other way the word ‘freak’ is used, is to describe a state of mind. “I freaked out”, that means, I couldn’t cope, I went berserk. And, “Something freaky happened”; it was surprising, unexpected and strange. So from this point on when the word freak is used, I am not using it in relation to these contemporary definitions, but rather in relation to a historical reference.

“ The modern freak show was a response to the growing mass market for amusements generated by urbanisation and economic growth. The New York City entrepreneur P.T. Barnum (1810-91) pioneered the modern exhibition of physically anomalous individuals at his American Museum, a popular, inexpensive pleasure palace. For the next century, in its various guises, the freak show remained a widely proliferated, popular, and highly conventionalised form of amusement in both Europe and North America. By 1950 because of a combination of the new, medicalized understandings of physical anomalies, the growth of concern for minority rights, and the rise of alternative forms of amusement such as television and the movies, the freak show had begun to decline.”(37) The preoccupation with those who are different from ourselves has been with us for most of human existence, either through ethnic difference, birth defects or any number of other more subtle reasons. It is thought that perhaps this is so because we fear being different to those around us that we do not want to stand out, (this is also a fear of those with the disability, “that the only way he would be able to make a living would be displaying himself in a sideshow.”(38)) Also, those who display difference can act as a reflection of what we fear we may become. The fragility of the human body also is apparent and becomes interesting and scary.

This chapter has turned out completely differently from how I would have imagined eighteen months ago. Originally I would have written about specific “freaks” and I imagine I may not have been so sensitive to the subject matter as I am now. It may have made more ‘entertaining’ reading, but this is where I’m at now with this subject. I expect this transformation in thinking is what research is about.

The Careers of People Exhibited in Freak Shows: The Problem of Volition and Valorization by David A. Gerber is an essay taken from the above-mentioned book. In this article Gerber discusses the concept of the right of consent and choice in relation to a book written by Robert Bogdan called Freak show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (1988). I have not read Bogdan’s book myself, only extracts presented by Gerber for use in this discussion.

On the face of it, Bogdan’s approach seems reasonable. When his five-point definition is investigated, I think he gives a lot of credit to the intellect of the common man circa 1840-1940.

‘Freak’ it seems was a broad way of grouping a lot of different physical types together under one literal banner. According to Bogdan, ““Freak” is an invention or construct, not a person, so the display of such people is not an offense to humanity but, more or less, show business.”(39) This is a logical and reasonable explanation. It separates ‘freak’ from the individual and is used in a way like ‘vaudeville’ is used as a description of a performance. The problem for me is, if a person works for a vaudeville show, that makes them a vaudevillian. If a person works for a freak show, it would make them a freak. So in reality one cannot separate the ‘humanity’ from the construct. Point two is, “historically the freak show has constituted a legitimate performance, because it was consciously staged for commercial and artistic success”.(40) I have no argument with this statement, however, point three, “the freak show ultimately was founded upon the willing participation of those displayed, the majority of whom were “active participants” in creating their presentations and found value and status in their roles as human exhibits”.(41) There are troubling combinations of words in this sentence. Willing participation, active participants, value and status and human exhibits. Firstly, this doesn’t match the first point where Bogdan says ‘freak’ is a construct, not a person, and here he says there is willing and active participation and value and status to be a human exhibit. Willing and active participation does not sit well with me.

“ Choice and consent continue to be problematic precisely because of the role of circumstances, such as the accident of the social situation into which we are born, in our lives, and because we are not equal in power to influence the course of our lives or even to understand them”.(42) Even the most educated, healthy individuals make bad decisions sometimes. So is the choice ‘actively’ positive when a person suffering a disability worthy of the freak show decides, “that’s the life for me?” The decision is not a fair one. Does the individual have more than one source for an income? Has the individual got all the correct information and understand it? Do they have enough time to decide? Is the individual being pressured or bullied into their decision? Is the individual in a situation where s/he can decide not to choose? These are very important factors in choice, ones that contemporary society may take for granted.

The ‘value and status’ perspective that Bogdan takes is obviously one of taking freak show participants stories at face value. If one is making choices about ones life without all the information or support as the above paragraph illustrates, then of course the individual will know nothing else, and hopefully would make the best of things, as is human nature. It seems a common thread among freak show performers that they saw themselves not as victims, but rather held their audience in contempt. The audience were the victims as they were the ones parting with their money. Sex workers defending their profession and their choice to persevere in this line of employment also use this argument. The value and status alluded to by Bogdan is rather tenuous. There may have been value and status from within the freak show, among co-workers. But I really do not think that value or status existed out side that arena.

As far as Bogdans statement “we need to question our assumption that we have a legitimate claim to argue with and condemn the choices, such as participating in a freak show, of those who lived in other historical epochs, especially when they saw no moral issue in their activities”(43). If social history is not looked back on with out a sense of moral judgement, the way we move into the future can have a precarious aim and outcome. Just because Bogdan doesn’t think we have a legitimate claim to pass judgement over those who lived during a different time, certainly doesn’t mean that we can’t and shouldn’t. Above all, I find it difficult to believe that those involved in the participation of freak shows found no moral dilemma in that participation.

And finally, “the freak show is a long gone phenomenon, so it is useless to condemn it.”(44) Even though it may seem like an extreme comparison, the Second World War and the atrocities delivered to people with disabilities, gypsies, the elderly and of course the Jews, also happened a long time ago, does that mean that it is also useless to condemn that?

I may be taking a hard line with Bogdans point of view, but I believe that it is this kind of insidious sentiment that keeps tabloids and voyeuristic television flourishing. I am not passing moral judgement on the fact that all this still exists in a different form, because I am just as guilty as the next person of looking. I am suggesting that one should take into account what is this kind of ‘entertainment’ actually providing society with? It’s easy to imagine in the future, a similar passage to Bogdan’s being written about the tragedy of Michael Jackson or Pamela Anderson. Most of the points listed by Bogdan could directly relate to them. So it seems the freak show is rolling on, so is it useless to condemn it?

Looking

Looking and seeing are more complicated than merely opening your eyes and casting them around. Our thoughts and sense of purpose direct all looking. “We are either looking at something, looking away or looking for something. Of course, there are the other kinds of looking that involve looking forward to something, which is an abstract concept of looking.”(45) When we are looking around, everything we see is affected by our thoughts, our individual backgrounds and experience. So why do pictures of sideshow freaks or other kinds of spectacles make us so curious that we must look and stare? I think it is because we feel it could be dangerous, it seems wrong, so if we can have a good look and no one knows, we won’t fear being judged by others. During a time in history when it was common to go to a sideshow or some other vaudevillian type of entertainment, people didn’t think twice about what they were looking at. Their ‘entertainment’ had been presented to them as fun and or educational, scientific even. I expect they thought they might have learnt something.

“Ultimately, seeing alters the thing that is seen and transforms the seer. Seeing is metamorphosis, not mechanism”.(46)

I understand this in a way that becomes overwhelming. For example, I am sitting at my kitchen table looking at the debris. I look at the phone and see the face of the person who I want to call me back. I look again and see the newest phone number inserted in the window used for numbers, I’ve had the same phone while living in three different houses, and in my mind see where the phone used to live in each of those houses. My phone is just a Telstra issue phone. Without even knowing, the phone turned into my friend and then took me back to my old houses. If I look around at everything on my kitchen table, each object can do a similar thing. This is why it is an overwhelming concept.

When looking at an object, the kind of processes the eyes engage in become part of a process that leads to a kind of dream. You may start imagining yourself using that object. So it seems the eyes are vehicles in dreaming and imagining. The object itself actually metamorphosis’s into a string of objects and situations.

Vision is a more analytical and anatomical process of the eyes, that is important to actually looking, even though this has a limited influence of perception. I have problems with my vision, and I don’t wear my glasses all the time. My stigmatism allows me to see the world with all the sharp edges taken off. I can see objects clearly, but often without any internal detail. For example, I can see a tree and its leaves, but I cannot see each individual leaf. My vision problem also affects the intensity of colour that I see. It can be assumed that everyone sees differently, and that is not even taking into account any experiential or emotional factors that influence sight.

Why do we look?

When I want to stare at a person, I don’t want them to know, as I do not want them to feel uncomfortable. To spy is a comfortable position for all parties. When confronted with unusual people, children stare until an adult notices and tells them to stop, it is considered rude to stare. This conditioning works very well, as adults we tend to be very polite and generally take a short, but intense look at those who are either very beautiful or extremely unusual. We have trained our selves to take in information at a rapid rate. We have to look. What the brain does with this gleaned information is debatable. I feel as though a classification and ranking process goes into affect. ‘Is that the strangest person I have ever seen? The most beautiful?’ there is also a comparison making process, ‘that person is very fat, am I that fat?’ It is though as humans we are on a quest to see as much as possible, it is like a permanent research assignment on humanity.

Freak shows allowed people the permission to stand and stare and examine to their hearts content. If you didn’t have long enough the first time, you could pay and look again. In contemporary society it’s really not acceptable to follow people around and look at the all day long, so TV is a way of participating in a similar way to freak show audience. For example, the Michael Jackson documentary produced by Granada Television featuring correspondent Martin Bashir (aired during 2003) gained such high ratings that it had an encore presentation. People, (myself included), were compelled to watch, and to see and hear this generations most famous freak. The act of looking in this circumstance involved an element of bewilderment, how could a person deliberately make himself look so strange and deny the fact? The process of seeing can provide comfort and can hurt. Seeing Michael Jackson transform from an attractive Afro-American man into vampiric and doll-like hurts the eyes, one wants to close the eyes and turn away. Looking and seeing are similar, but not the same. Looking skims the surface and allows us enough information to get from one point to another. Seeing gives us understanding and feeds the imagination.

“Ultimately, seeing alters the thing that is seen and transforms the seer. Seeing is metamorphosis, not mechanism”.(46)

I understand this in a way that becomes overwhelming. For example, I am sitting at my kitchen table looking at the debris. I look at the phone and see the face of the person who I want to call me back. I look again and see the newest phone number inserted in the window used for numbers, I’ve had the same phone while living in three different houses, and in my mind see where the phone used to live in each of those houses. My phone is just a Telstra issue phone. Without even knowing, the phone turned into my friend and then took me back to my old houses. If I look around at everything on my kitchen table, each object can do a similar thing. This is why it is an overwhelming concept.

When looking at an object, the kind of processes the eyes engage in become part of a process that leads to a kind of dream. You may start imagining yourself using that object. So it seems the eyes are vehicles in dreaming and imagining. The object itself actually metamorphosis’s into a string of objects and situations.

Vision is a more analytical and anatomical process of the eyes, that is important to actually looking, even though this has a limited influence of perception. I have problems with my vision, and I don’t wear my glasses all the time. My stigmatism allows me to see the world with all the sharp edges taken off. I can see objects clearly, but often without any internal detail. For example, I can see a tree and its leaves, but I cannot see each individual leaf. My vision problem also affects the intensity of colour that I see. It can be assumed that everyone sees differently, and that is not even taking into account any experiential or emotional factors that influence sight.

Why do we look?

When I want to stare at a person, I don’t want them to know, as I do not want them to feel uncomfortable. To spy is a comfortable position for all parties. When confronted with unusual people, children stare until an adult notices and tells them to stop, it is considered rude to stare. This conditioning works very well, as adults we tend to be very polite and generally take a short, but intense look at those who are either very beautiful or extremely unusual. We have trained our selves to take in information at a rapid rate. We have to look. What the brain does with this gleaned information is debatable. I feel as though a classification and ranking process goes into affect. ‘Is that the strangest person I have ever seen? The most beautiful?’ there is also a comparison making process, ‘that person is very fat, am I that fat?’ It is though as humans we are on a quest to see as much as possible, it is like a permanent research assignment on humanity.

Freak shows allowed people the permission to stand and stare and examine to their hearts content. If you didn’t have long enough the first time, you could pay and look again. In contemporary society it’s really not acceptable to follow people around and look at the all day long, so TV is a way of participating in a similar way to freak show audience. For example, the Michael Jackson documentary produced by Granada Television featuring correspondent Martin Bashir (aired during 2003) gained such high ratings that it had an encore presentation. People, (myself included), were compelled to watch, and to see and hear this generations most famous freak. The act of looking in this circumstance involved an element of bewilderment, how could a person deliberately make himself look so strange and deny the fact? The process of seeing can provide comfort and can hurt. Seeing Michael Jackson transform from an attractive Afro-American man into vampiric and doll-like hurts the eyes, one wants to close the eyes and turn away. Looking and seeing are similar, but not the same. Looking skims the surface and allows us enough information to get from one point to another. Seeing gives us understanding and feeds the imagination.

Drawings. -The influence of cinema

I have also been influenced by the sequential narrative nature of the cinema. I enjoy looking in film journals (Cantrills Filmnotes), and books about filmmaking. The stills often tell their own story rather than glamorous publicity photographs. In a way the actors become trapped in their character in a film still. I like this idea as a way of viewing my drawings. When I was a child, I thought that all the different people on television were actually tiny people living inside the television set. Of course I was surprised when my Dad had to take the back off the TV and the tiny people did not come running out. As a visual artist I have the ability to create a world or worlds where I can pick out a particular character and enlarge him or her to make them the focus or push them far into the background, so no one can see them. Filmmakers employ these visual treatments as well. I have developed some symbols within my work that has developed into a visual language in which I can communicate my visual ideas.

I use two characters, they are my actors, and they are male and female and can represent the different roles I wish to portray from my personal experience. I include props, which can represent a setting, combining lighting in the form of shadows to help define atmosphere.

The influence of cinema is evident in the way my series of drawings can be viewed; more detail is discussed in the chapter specifically about my drawings.

I use two characters, they are my actors, and they are male and female and can represent the different roles I wish to portray from my personal experience. I include props, which can represent a setting, combining lighting in the form of shadows to help define atmosphere.

The influence of cinema is evident in the way my series of drawings can be viewed; more detail is discussed in the chapter specifically about my drawings.

Circles

I have an interest in the circle as a visual device and as a symbolic prop in my work. I think of in terms of being inclusive as well as exclusive, representing a whole. The circle can also be a sphere, like a world or a ball to play with. Two circles over lapping represents another train of thought for me, firstly where two circles over lap there is a connection of two wholes, like a ‘bumping’ into someone coincidence, I secretly refer to this as a circle of fate, fate circles. The fate circles work in a way that allows for second chances, if “it” doesn’t work out this time hopefully next time the fate circle comes around “it” will. This works very well translated into visual work because I can just draw the circle in and it can remain part of my own visual vocabulary, without being overly illustrative of a concept. Secondly I see the part where two circles over lap in a way that was described to me by Dr Cunningham Dax, as the part where the artist and the psychiatric patient share some common ground. In Roger Cardinal’s book Outsider Art, he refers to Lombroso’s study Genio e follia (1882) that was the first significant study of mental disorders and creativity. Lombroso claimed through his study that artists were “ten times more prone to mental disorders than average man.” (47)I find this interesting and relevant because I have wandered around in that overlap in the past. That overlap is an effective way to depict emotional states, a combination of two elements and keeping them separate entities as well.

About My Drawings

Making drawings is intrinsic to my work practice. These drawings are made on watercolour paper and cartridge paper. I have an intuitive approach, where I often start by making random marks with an idea in mind. These marks are made with ink, diluted watercolour or pencil. Colours or tone are built up and shapes are refined and then worked into to create detail, and then sometimes gesso is applied to block areas out. The theme of this work has been mainly about the act of performing. For example, a figure on a stage with a costume on and props to aid the performance. Stories about circus life I find very inspirational, “Lennie the Monkey- Jockey Act, …Just after the python died, Lennie died too…In came the pony with Lennie riding as surely as he ever had. Lennie was crouched low in a little saddle made especially for him… It used to give me the shudders to see the ghost of Lennie riding around the ring as pert and as cheeky as ever. I was relived when he did collapse, in the middle of a show(48)…” Tightropes, bunting flags, balancing and contortion have featured. I use the setting of inside the big top, often with a spot- light defining the space in which the character is performing; usually there are lots of circles present in these compositions.

Black and white Ink Drawings

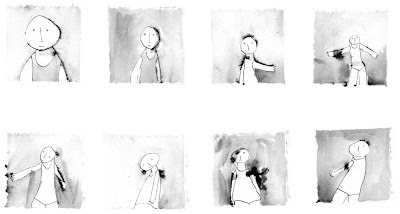

The series of drawings I have made are depictions of a man and woman. I have used the idea of creating a kind of storyboard with these pictures on each sheet of paper. During my research I have come across books relating to cinema, cinema studies as well as books about record cover art. The subjects of these books lead to a natural format of a lot of small squares or rectangles in sequential order describing a scene from a movie or a series of cover art from a particular artist or record company.

The actual appearance of these pages with their patterned display of images, I found very visually appealing. And as a result I have added that to my aesthetic taste.

I have been making black and white drawings with a pen and ink. These pictures are a little like a storyboard for the theatre, or perhaps like a few frames from a piece of film. The drawings are in groups of eight and the images in these drawings come from my imagination. The characters are both men and women, dressed in stripy t-shirts, leotards or dress. The men and women in these pictures seem to be either back stage waiting to go on, or in a rehearsal or in their own private world looking at themselves in a mirror. They exist in a non-space with rarely any identifying landscape, sometimes a road or something in the sky. I enjoy making these drawings because; repeating the same character helps develop the personality of the subject. By bringing the subject up close or pushing it far into the background the dynamics of the picture change. For me this creates the opportunity to explore the potential of each drawing. I am working the compositions inside a square of seven centimetres; this size suits me well, as I like to create intimate little drawings about fragile, introspective, emotional characters. I don’t believe in trying to reproduce aspects of reality, or the every-day. I like my work to be an escape from the every-day. From time to time I would like to get inside and walk around my pictures just to get away from the every-day.

I believe as a human being, I see the world (obviously) in my own way. As my work deals with the human condition, my point of view of that “condition” would be uniquely mine, (I would imagine). So, as an insight into what that would be, let me explain here. Firstly, I think, (as Shakespeare wrote), the world is a stage and we are all actors upon it. My interactions with friends, family and people I meet and work with all have some kind of impact on me as I imagine I do on them. Stories are told to each other, happy and unhappy. History repeats itself and fables get built. I have a huge problem with fakeness in character; of course there is nothing I can do about it, except make honest artwork. What I mean by honest is, not trying to trick the viewer into believing that they are looking at a masterpiece when they clearly are not. My pieces are meanderings in my imagination aided by a significant amount of looking and reading.

The actual appearance of these pages with their patterned display of images, I found very visually appealing. And as a result I have added that to my aesthetic taste.

I have been making black and white drawings with a pen and ink. These pictures are a little like a storyboard for the theatre, or perhaps like a few frames from a piece of film. The drawings are in groups of eight and the images in these drawings come from my imagination. The characters are both men and women, dressed in stripy t-shirts, leotards or dress. The men and women in these pictures seem to be either back stage waiting to go on, or in a rehearsal or in their own private world looking at themselves in a mirror. They exist in a non-space with rarely any identifying landscape, sometimes a road or something in the sky. I enjoy making these drawings because; repeating the same character helps develop the personality of the subject. By bringing the subject up close or pushing it far into the background the dynamics of the picture change. For me this creates the opportunity to explore the potential of each drawing. I am working the compositions inside a square of seven centimetres; this size suits me well, as I like to create intimate little drawings about fragile, introspective, emotional characters. I don’t believe in trying to reproduce aspects of reality, or the every-day. I like my work to be an escape from the every-day. From time to time I would like to get inside and walk around my pictures just to get away from the every-day.

I believe as a human being, I see the world (obviously) in my own way. As my work deals with the human condition, my point of view of that “condition” would be uniquely mine, (I would imagine). So, as an insight into what that would be, let me explain here. Firstly, I think, (as Shakespeare wrote), the world is a stage and we are all actors upon it. My interactions with friends, family and people I meet and work with all have some kind of impact on me as I imagine I do on them. Stories are told to each other, happy and unhappy. History repeats itself and fables get built. I have a huge problem with fakeness in character; of course there is nothing I can do about it, except make honest artwork. What I mean by honest is, not trying to trick the viewer into believing that they are looking at a masterpiece when they clearly are not. My pieces are meanderings in my imagination aided by a significant amount of looking and reading.

Tapestries. My drawing, a tapestry aesthetic?

As a tapestry weaver I am familiar with the concept of narrative, due to my interest in the history of tapestry. Often within a medieval tapestry, for example…. a ribbon with text on it would be used as a compositional as well as a communication device to link the images and the events contemporary to the times. (This is an early representation of the speech bubble, like comics.) A central character may also be repeated in different aspects within a piece to help convey time passing in a story.

The actual appearance of drawing used as a starting point for tapestry often does not contain many of the details that would appear in the tapestry and vice versa. I make many decisions while working on the loom, rather than having everything worked out before beginning the tapestry. I expect that some of the drawings look very bare of detail, even though they are not all going to become tapestries I do think that drawing for tapestry can have an effect on how finished a drawing can look.

I use minimal text in my work, as opposed to my reference earlier about medieval tapestry, as I believe in leaving images ambiguous. I think if there is enough information available in a drawing or tapestry, the viewer can make their own interpretation of what they see.

The actual appearance of drawing used as a starting point for tapestry often does not contain many of the details that would appear in the tapestry and vice versa. I make many decisions while working on the loom, rather than having everything worked out before beginning the tapestry. I expect that some of the drawings look very bare of detail, even though they are not all going to become tapestries I do think that drawing for tapestry can have an effect on how finished a drawing can look.

I use minimal text in my work, as opposed to my reference earlier about medieval tapestry, as I believe in leaving images ambiguous. I think if there is enough information available in a drawing or tapestry, the viewer can make their own interpretation of what they see.

Tuesday, August 11, 2009

Why does tapestry differ from painting?

What quality can I create by making tapestry and not leaving my paintings as paintings?

Paint occupies an important part of my process of creating. It is important as a tapestry artist to be able to make a lot of pictures and to be able to work through a lot of ideas (or one), and make good use of time not at the loom. I enjoy working on paper; the immediacy of mark making, and the seductive quality of watercolour doing things on the paper is great. Some of the painterly effects that are only possible on paper can often suggest compositional blobs and marks that I would never have used had there not been a painting process before weaving. This does not mean that I attempt to recreate a water- mark with weaving. On the contrary, I actually cannot abide the slavish way that some tapestry weavers aim for this type of affect. Tapestry offers its own set of intrinsic and dynamic marks that are visually interesting on there own terms. By using a combination of marks (passes, half-passes, mixed and unmixed bobbins), colours and materials it is possible to create a lively surface that can offer more than a painting. The amount of time that is used contemplating while working on a tapestry also allows for small and consistent decisions to be made, I think there is something in this that painting does not have. Once an area is woven, it is not so common that the area will be worked on again, that area will be left and woven over the top of. If something has gone wrong or looks funny in one part of the tapestry it can be fixed by weaving something a little differently further along. This way of working I think is peculiar to weavers, so far I have not come across this with any other art form. These processes lead to intensity within the image that I believe are not possible with paint alone.

Paint occupies an important part of my process of creating. It is important as a tapestry artist to be able to make a lot of pictures and to be able to work through a lot of ideas (or one), and make good use of time not at the loom. I enjoy working on paper; the immediacy of mark making, and the seductive quality of watercolour doing things on the paper is great. Some of the painterly effects that are only possible on paper can often suggest compositional blobs and marks that I would never have used had there not been a painting process before weaving. This does not mean that I attempt to recreate a water- mark with weaving. On the contrary, I actually cannot abide the slavish way that some tapestry weavers aim for this type of affect. Tapestry offers its own set of intrinsic and dynamic marks that are visually interesting on there own terms. By using a combination of marks (passes, half-passes, mixed and unmixed bobbins), colours and materials it is possible to create a lively surface that can offer more than a painting. The amount of time that is used contemplating while working on a tapestry also allows for small and consistent decisions to be made, I think there is something in this that painting does not have. Once an area is woven, it is not so common that the area will be worked on again, that area will be left and woven over the top of. If something has gone wrong or looks funny in one part of the tapestry it can be fixed by weaving something a little differently further along. This way of working I think is peculiar to weavers, so far I have not come across this with any other art form. These processes lead to intensity within the image that I believe are not possible with paint alone.

Does the use of materials make the flat surface more interesting?

Materials I use to weave with are very important for all kinds of reasons. I prefer to use materials that are special in some way. Whether they are very old, exotic or precious like silk, these factors can sometimes influence what I might make with them. I don’t often feel this sense of coveting with paper (although I do love my paints). Some yarns such as silk do carry a luminosity that is impossible to recreate with any other material. I have also noticed that some interesting things happen within a tapestry when using different materials. Even though tapestry is for all intents a flat medium, using wool and cotton in different parts of the tapestry can help create a sense of depth by alluding to one part being in front of the other.

I like to use materials that may have already had a life. A few years ago I was lucky enough to be given box filled with antique threads and materials from Japan. Since then, I have tried to collect as much exotic materials as possible. Besides being interesting to look at, they are fun to use because I feel like I am giving them a new life as a tapestry.

I like to use materials that may have already had a life. A few years ago I was lucky enough to be given box filled with antique threads and materials from Japan. Since then, I have tried to collect as much exotic materials as possible. Besides being interesting to look at, they are fun to use because I feel like I am giving them a new life as a tapestry.

There is density of image and colour that is unique to tapestry, is it due to an added textural quality?

The intrinsic nature of a woven surface embodies a certain amount of texture. These ‘beads’ of colour, (this is the description of the woven shape caused by passing the wool/yarn over and under the warps of a tapestry), create the texture seen in the surface. Each bead contains a certain amount of reflective properties that increase the intensity of its colour when woven either, in a patch or a small amount on it’s own. This colour, (let’s say its yellow), will also react differently when it is woven next to any other colour, the theories of colour can be applied directly when weaving. If strands of yellow and blue are gathered together and woven, a kind of green will be seen to emerge, but still it will always be yellow and blue. This is called optical mixing, and from this point on it would be possible to write thousands of words on the subject, so I will stop now and leave that to someone else.

The density of image is also a quality within tapestry that I find interesting. When drawing or painting one is always faced with the surface of paper or canvas, usually white. When making a tapestry all that is faced is the skeleton of vertical warps. The image is built little by little over the warps, the yarn is taken over and under the warps, and using a bobbin the weft is beaten down to cover the warps and at the same time the image reveals itself. There is no visual trace of the colour of the warps, only their ribbed texture. Unlike drawing or painting, the colour, surface and the canvas or paper itself is almost always still a part of how we see the images presented. When interpreting my images, I decide whether or not I will take notice of the texture of the paper and the look of a dry brush across it surface. I could just as easy weave it a solid patch of pale colour.

My approach to make tapestries.

I work in a journal regularly and this is where most of my images come from. The tapestries are finely woven pieces; they feature the theme of the circus and fair ground. I have made both fine and course tapestries; I believe that the very small, fine works are most successful.

This is where the precious nature of the silks and cottons can be appreciated more if they are used alone. This is why I weave fine pieces; beside the reason that the work becomes more like a diary entry and can represent smaller ideas than a bigger piece I am working on. Drawings in my journal are often re-worked into more substantial drawings and tapestries. I like the connection between circus, sideshow and tapestry because, so much of what we identify about these subjects can directly be related to the textile nature of the circus tent, side show banners and the costumes. It seems to be in keeping to weave sections and interpretations of these elements. These small tapestries are portraits of tightrope walkers, equestriennes and stage performers in circus settings.

I believe I keep making work about this subject (for more reasons than this being my topic) because I feel, as humans we act out all the time. I find the metaphors connected with the circus particularly befit humans. The way we walk a tightrope, walk a fine line, run rings around… take centre stage, (in relation to contortion) bending over backwards for someone, have a ringleader. Mainly this connection is based upon language; yet, the clowns (I’m not doing clowns by the way) tend to visually represent exaggerated human behaviour. Just as Hieronymus Bosch illustrated common language and ideas of his time, I think my images could offer a similar way of understanding ourselves.

The density of image is also a quality within tapestry that I find interesting. When drawing or painting one is always faced with the surface of paper or canvas, usually white. When making a tapestry all that is faced is the skeleton of vertical warps. The image is built little by little over the warps, the yarn is taken over and under the warps, and using a bobbin the weft is beaten down to cover the warps and at the same time the image reveals itself. There is no visual trace of the colour of the warps, only their ribbed texture. Unlike drawing or painting, the colour, surface and the canvas or paper itself is almost always still a part of how we see the images presented. When interpreting my images, I decide whether or not I will take notice of the texture of the paper and the look of a dry brush across it surface. I could just as easy weave it a solid patch of pale colour.

My approach to make tapestries.

I work in a journal regularly and this is where most of my images come from. The tapestries are finely woven pieces; they feature the theme of the circus and fair ground. I have made both fine and course tapestries; I believe that the very small, fine works are most successful.

This is where the precious nature of the silks and cottons can be appreciated more if they are used alone. This is why I weave fine pieces; beside the reason that the work becomes more like a diary entry and can represent smaller ideas than a bigger piece I am working on. Drawings in my journal are often re-worked into more substantial drawings and tapestries. I like the connection between circus, sideshow and tapestry because, so much of what we identify about these subjects can directly be related to the textile nature of the circus tent, side show banners and the costumes. It seems to be in keeping to weave sections and interpretations of these elements. These small tapestries are portraits of tightrope walkers, equestriennes and stage performers in circus settings.

I believe I keep making work about this subject (for more reasons than this being my topic) because I feel, as humans we act out all the time. I find the metaphors connected with the circus particularly befit humans. The way we walk a tightrope, walk a fine line, run rings around… take centre stage, (in relation to contortion) bending over backwards for someone, have a ringleader. Mainly this connection is based upon language; yet, the clowns (I’m not doing clowns by the way) tend to visually represent exaggerated human behaviour. Just as Hieronymus Bosch illustrated common language and ideas of his time, I think my images could offer a similar way of understanding ourselves.

Developing a collage cartoon for a tapestry.

The approach I take is to create an evolving image where very little is resolved at the start. I have begun other work with this approach, where imagery is made up fresh every day and added to the work to create a larger piece. The work that I am referring to is a scroll like weaving that I have been working on for a very long time. With that piece, I decided that the background would be all tones of red, and the figures that were added daily would be superimposed upon it, this is ongoing and not part of my MA work. I found it an interesting way of building an image and decided to include it into this new work. The present collage has two methods unifying the image. The first way is that the entire background colour was drawn from a patched together collage of different greens. That patchwork of green was then be placed behind the warps whenever background is to be woven. The second unifying element is a continuous line of bunting flags. This created an atmosphere of a fair or carnival. I have collected characters from journals and paintings that incorporated into the collage. Other visual sources include images taken from books that are about the circus and performance. The small images have been manipulated on a photocopier to gain the correct scale, cut out and placed onto a large sheet of paper. When a pleasing composition is established the images were stuck down with tape. I tried to create a kind of narrative space. The work has an unusual and confusing sense of non-perspective. It can seem as though it is an aerial perspective because of the patches of colour; the figures within the tapestry confuse the scale and the spatial relationships. This had not been my conscious intent; although I knew something unpredictable would be the result. The bunting flags mentioned earlier also adds to the narrative, the flags wind up or down (depending on how one views the picture) compressing the perspective in a way that describes the narrative in a similar way to “Indian miniatures from Rajasthan”(49) are sometimes constructed. I am particularly fond of this style of composition, because I see relationships between medieval art and tapestry.

Conclusion

Conclusion

My work practise has gained more depth due to the process of investigation. I have been exposed to many stories and images through research that has informed my work. I make work from an intuitive and personal position, through the research I have had much more to draw upon. I have a thorough understanding of my subject now, and this has brought a sense of sophistication to my image making. I have refined detail and shapes to create more iconic images.

I discovered that having a topic to make work around was stabilising, but I was still drawn to make work about my own experiences. I had originally hoped to have an emphasis on historical records, but soon realised that I couldn’t make work in that way. To conclude, this body of work illustrates a dialogue between my interest in the carnivalesque which informs my own experiences.

My work practise has gained more depth due to the process of investigation. I have been exposed to many stories and images through research that has informed my work. I make work from an intuitive and personal position, through the research I have had much more to draw upon. I have a thorough understanding of my subject now, and this has brought a sense of sophistication to my image making. I have refined detail and shapes to create more iconic images.

I discovered that having a topic to make work around was stabilising, but I was still drawn to make work about my own experiences. I had originally hoped to have an emphasis on historical records, but soon realised that I couldn’t make work in that way. To conclude, this body of work illustrates a dialogue between my interest in the carnivalesque which informs my own experiences.

End notes

[1] Carmel Bird, Exit Queen Victoria. p167 Meanjin 2002

[1] Roger Sabin. Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels. A history of comic art. p.8, 9. Phaidon Press Inc. London. 1996

[1] Scott McCloud. Understanding Comics, the Invisible Art P.7 Kitchen Sink Press Inc. 1993

[1] Ibid., \p.30-41

[1] Sasha Grishin. Andrew Sibley, Art on the Fringe of Being. Craftsman House. 1993 p.8

[1]Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.39

[1] Ibid., p.39

[1] D. Bax. Hieronymus Bosch, his picture writing deciphered. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam, 1978. p. XV

[1] Ibid. p.2

[1] Ibid. p370.

[1] Ibid p.16

[1] ibid p. 18

[1] Ibid. p. 18

[1] R. H. Marijnissen, M. Seidel, Bruegel. Artabras Book Published by Harrisson House 1984. p. 13

[1] Ibid. p. 17

[1] Ibid. p. 16,17

[1] Ibid. p.107

[1] Ibid. p. 43

[1] F. P. Thomson. Tapestry: Mirror of History. The Jacaranda Press 1980. p. 83

[1] Barty Phillips. Tapestry. Phiadon Press Limited. 1994. Frontispiece. Colour images of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries.

[1] Henry Glassie. The Spirit of Folk Art, The Girard Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art. Harry. N. Abrams. Inc. Publishers, New York. 1989. p24

[1] Ibid. p. 26

[1] Ibid. p. 26

[1] Ibid. p. 31

[1] Ibid . p..36

[1] Ida Rodriguez-Prampolini. P.50 Erika Billeter. Images of Mexico, the Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas. 1987

[1] Ibid. p.50

[1] Ramon A. Gutierrez, Conjuring the Holy. Home Altars of Mexico, Dana Salvo. Thames and Hudson. 1997

Outsider Art

[1] Michel Thevoz. Art Brut. Booking International. 1995. p.11

[1] Roger Cardinal. Outsider Art. Preager Publishers, Inc. New York, 1972. p.14

[1]Ibid., p.15

[1]Rosemarie Garland Thomson. Introduction: From Wonder to Error- A Genealogy of Freak Discourse in Modernity. Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body edited by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, New York University Press 1996. p.4

[1]Rosemarie Garland Thomson. p.4

[1] David A. Gerber, p.42

[1] Ibid. p.46 A soldier from the Second World War, Harold Russell had both hands amputated during military training, this statement was common amongst those who had suffered injury as freak shows were still in operation. Harold Russell went on to improve working rights for those also had suffered disabilities.

[1] David A. Gerber. The Careers of People Exhibited in Freak Shows: The Problem of Volition and Valorization. Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body edited by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, New York University Press 1996. p.39

[1] David A. Gerber.p.39

[1] Ibid. p.39

[1] David A. Gerber. p.41

[1] Ibid. p39

[1]Ibid. p..39

[1] James Elkins. The object Stares Back. Simon and Schuster 1996. p.22

[1] ibid. p 11,12.

[1] Roger Cardinal. Outsider Art. Preager Publishers, Inc. New York, 1972 (general reference)

[1] Fred A. Lord. Little Big Top. p.23

[1] Andrew Topsfield. Court Painting in Rajasthan. Marg Publications. 2000

[1] Roger Sabin. Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels. A history of comic art. p.8, 9. Phaidon Press Inc. London. 1996

[1] Scott McCloud. Understanding Comics, the Invisible Art P.7 Kitchen Sink Press Inc. 1993

[1] Ibid., \p.30-41

[1] Sasha Grishin. Andrew Sibley, Art on the Fringe of Being. Craftsman House. 1993 p.8

[1]Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.8

[1] Ibid., p.39

[1] Ibid., p.39

[1] D. Bax. Hieronymus Bosch, his picture writing deciphered. A. A. Balkema, Rotterdam, 1978. p. XV

[1] Ibid. p.2

[1] Ibid. p370.

[1] Ibid p.16

[1] ibid p. 18

[1] Ibid. p. 18

[1] R. H. Marijnissen, M. Seidel, Bruegel. Artabras Book Published by Harrisson House 1984. p. 13

[1] Ibid. p. 17

[1] Ibid. p. 16,17

[1] Ibid. p.107

[1] Ibid. p. 43

[1] F. P. Thomson. Tapestry: Mirror of History. The Jacaranda Press 1980. p. 83

[1] Barty Phillips. Tapestry. Phiadon Press Limited. 1994. Frontispiece. Colour images of the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries.

[1] Henry Glassie. The Spirit of Folk Art, The Girard Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art. Harry. N. Abrams. Inc. Publishers, New York. 1989. p24

[1] Ibid. p. 26

[1] Ibid. p. 26

[1] Ibid. p. 31

[1] Ibid . p..36

[1] Ida Rodriguez-Prampolini. P.50 Erika Billeter. Images of Mexico, the Contribution of Mexico to 20th Century Art. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas. 1987

[1] Ibid. p.50

[1] Ramon A. Gutierrez, Conjuring the Holy. Home Altars of Mexico, Dana Salvo. Thames and Hudson. 1997

Outsider Art

[1] Michel Thevoz. Art Brut. Booking International. 1995. p.11

[1] Roger Cardinal. Outsider Art. Preager Publishers, Inc. New York, 1972. p.14

[1]Ibid., p.15

[1]Rosemarie Garland Thomson. Introduction: From Wonder to Error- A Genealogy of Freak Discourse in Modernity. Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body edited by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, New York University Press 1996. p.4

[1]Rosemarie Garland Thomson. p.4

[1] David A. Gerber, p.42

[1] Ibid. p.46 A soldier from the Second World War, Harold Russell had both hands amputated during military training, this statement was common amongst those who had suffered injury as freak shows were still in operation. Harold Russell went on to improve working rights for those also had suffered disabilities.

[1] David A. Gerber. The Careers of People Exhibited in Freak Shows: The Problem of Volition and Valorization. Freakery, Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body edited by Rosemarie Garland Thomson, New York University Press 1996. p.39

[1] David A. Gerber.p.39

[1] Ibid. p.39

[1] David A. Gerber. p.41

[1] Ibid. p39

[1]Ibid. p..39

[1] James Elkins. The object Stares Back. Simon and Schuster 1996. p.22

[1] ibid. p 11,12.

[1] Roger Cardinal. Outsider Art. Preager Publishers, Inc. New York, 1972 (general reference)

[1] Fred A. Lord. Little Big Top. p.23

[1] Andrew Topsfield. Court Painting in Rajasthan. Marg Publications. 2000

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)